Energy Economics and Financing: A Case of Developing and Emerging Economies

20 Aug 2024

Introduction

Today, there is no doubt that most developing countries continue to struggle with abject poverty and slow economic growth due to poor implementation of broad-based socio-economic development policies that promote manufacturing and agricultural production. Historically, the achievement of these goals occurs with a corresponding increase in energy use. Globally, about 79% of developing countries and 74% of Sub-Saharan African do not have access to modern electricity (Legros et al., 2009). Studies have continued to show that energy consumption is positively related to wealth. It is hypothesized that increased energy consumption is a fundamental condition for growth in developing countries.

In most parts of Africa, the energy sector is characterized by over-reliance on traditional biomass sources such as wood, crop waste, manure, charcoal, and unfledged energy sectors. This underscores the need for least developed Countries to device and implement policies aimed at increasing access to modern energy services. Africa has substantial renewable energy resource capacity that can meet the continent's electricity needs. These include hydropower, geothermal, abundant biomass, and significant wind and solar potential, yet the exploitation only contributes to 4% of total power generation in the world. This can be explained by technical, financial, and environmental challenges.

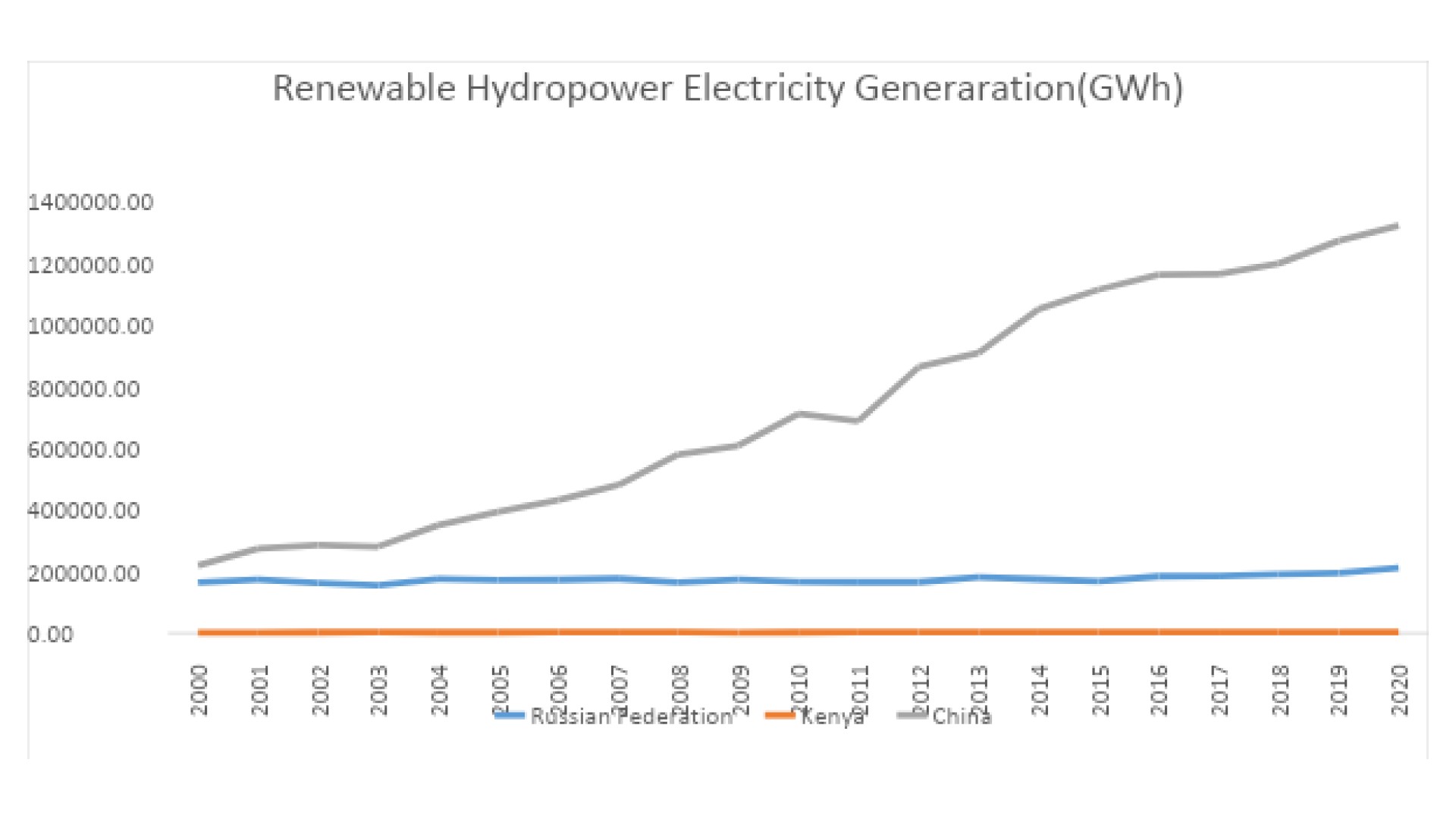

Figure 1

Source: IRENA (2022), Renewable Energy Statistics 2022, International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), Abu Dhabi.

Notes: Electricity generation (GWh) is the gross electricity produced by electricity plants, combined heat, and power plants (CHP) and distributed generators measured at the output terminals of generation. It includes on-grid and off-grid generation, and it also includes the electricity self-consumed in energy industries; not only the electricity fed into the grid (net electricity production).

Global Overview of Energy Economics

Economists have been intrigued by irrefutable evidence that suggest a causal relationship between energy consumption and growth in economies, and this is fueled by the notion that energy prices affect spending decisions of households, firms, and the overall performance of the economy. Emerging and developing economies have been exposed to various energy and economic sustainability challenges including lack of sustainable financial support, high dependence on imported energy, high energy prices and cost volatilities, technological and skilled labor. Due to this emerging framework, investments in clean energy production need momentous input and support from developed nations.

Since 2021, energy markets have been tight for various reasons including economic rebound following the pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, disrupted supply chain and climate changes. Oil prices did hit their highest and it was noted that as the price of natural gas rose, so did electricity in many markets. “Energy and Financial Market Interactions” authored by Shaiban et al. reveals how oil price shocks affect the performance of certain country-specific banking industries. The findings ascertain that oil price shocks have negative impacts on equity in banking indices in the emerging economies except Mexico. They recommend that international banking portfolio investors should consider hedging oil price risks.

The higher energy prices have led to high inflation, pushing families into poverty, curtailing manufacturing companies and closing some. For instance, Europe faced gas rationing during winter because of the historic dependence on Russia and the economic shock was felt throughout the continent and consequent trickle-down effect in Sub-Saharan Africa. Developing and emerging economies have been facing higher energy bills and fuel shortages, this has increased extreme poverty and set back progress towards achieving universal and affordable energy access.

Energy Financing

SDG 7 advocates for universal access to affordable, reliable, and modern energy services. To achieve this goal, technological and financial investment is required at a rate that by far exceeds historical levels. Sub Saharan Africa has approximately 31% electrification and the policy reforms are being poorly implemented, resulting in sprinkles of doubt as to whether the region will achieve 100% access to electricity by 2030.

Most developing countries face a hard-hitting challenge in attracting energy sector investments. Additionally, there is a general perception that regions like Africa contribute little to greenhouse gas emissions hence offers few opportunities to shrink these emissions, consequently missing appeal to climate finance projects.

National governments and stakeholders often declare provision of incentives to individuals pursuing off grid solutions, however, access has remained limited and nascent for sources like solar. The policies concentrate on enabling conditions for renewable energy elucidations with an assumption that private actors have access to finance. Nevertheless, they often lack the nuance and specificity of contextually informed impediments to success that an indigenous enterprise might manage.

Challenges and Opportunities in Africa’s Power Sector

Deficits and Investment Opportunities

Studies show that 80% of the world population without electricity mostly live in rural areas of sub-Saharan Africa. It is estimated that three in four Africans do not have access to electricity and this is worsened by chronic power shortages plague. Rural areas account for about seventy-five percent of the population yet only 15 % of this population live within a 10-kilometer radius of a substation. This implies that only a small proportion can be added to the electricity grid at a relatively low cost.

High Cost of Producing power in Africa

The average cost of power production in Africa is exceptionally high. This is due to the small scale of most state power systems and the widespread dependence on costly oil-based generation. Others include less than 100% implementation of fiscal budgets allocated for energy investment, insufficient maintenance, losses, and inefficiencies occurring during distribution phase, and pricing of electricity less than the cost, which encourages wasteful consumption. If regional power trade became a reality, generation costs would fall, and full cost-recovery tariffs would be priced in much of Africa.

Finance sources and Private Sector role in Financing Clean Energy

UN Environment Programme and Energy Finance

UNEP, through technical assistance and targeted financial support, helps the finance community to invest in the renewal energy and energy efficiency sectors. The unit brings together renewal energy project developers and “first mover” financiers to share early-stage investment costs and mitigate risks. In addition, UNEP activities aid in mobilizing new and further investments in clean energy end user finance through provision of knowledge and financial tools and capacity building of financial sector actors, government institutions and technology providers. UNEP also helps international climate finance for governments to achieve national low carbon development ambitions.

Potential Public Finances

While it is true that private sources play an increasingly key role in financing clean energy projects, the low returns to investors imply that a substantial portion of expenditures may need to be covered by public sources, which include emerging donors, domestic taxation, financing from carbon markets, aviation, and maritime taxation.

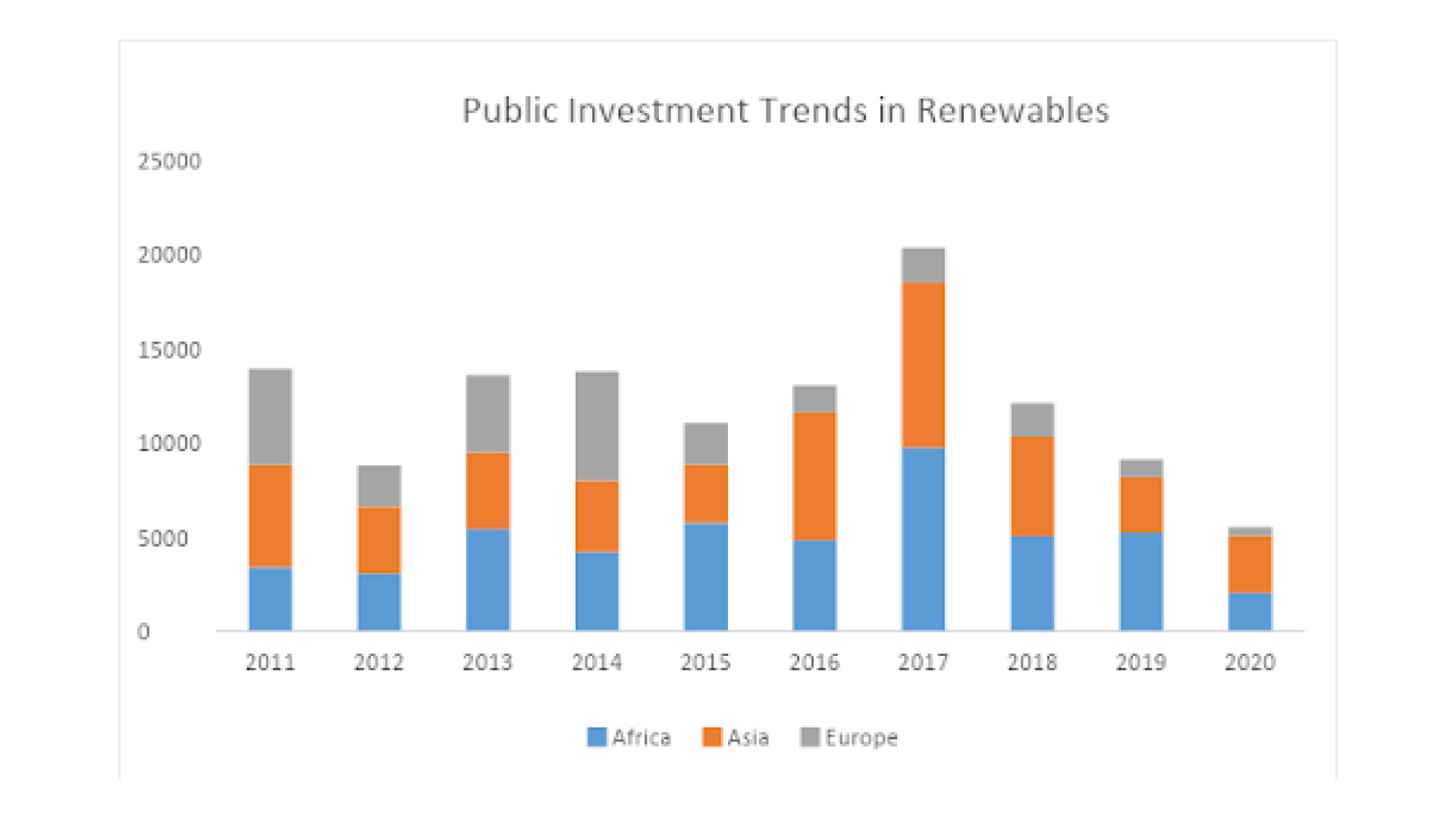

Figure 2

Source: IRENA (2022), Renewable Energy Statistics 2022, International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), Abu Dhabi

Notes: Amount in USD Million

Private Sector Assessment

Unlike public sectors, private financiers and developers consider specifications beyond transaction characteristics in making investment decisions. During project selection, they also look at wider legal, political, and economic contexts that govern a project.

Governments creating Public Private Partnership units are likely to attract more private investors. The resulting features are usually clear political support, proper legal and regulatory structures, and transparent procurement framework. All these lower uncertainties, risk profile, and improve project viability.

For renewable energy specifically, technical capacity is needed to properly cost and reflect the financial and economic value of environmental and natural resources. Documentation that suitably allocates price and risks to appropriate parties is essential to boost private investor confidence. This is only achievable when concession and off-take agreements are negotiated within a transparent charter governed by an independent regulatory authority.

Conclusion

Regional energy economic policies, especially for developed nations, affect least developed economies in that every basic need requires energy. Manufacturers to individual households need energy for daily operations and wealth creation. It is for this reason that OPEC countries like Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates thrive when oil prices skyrocket. Energy Financing in emerging economies remain squat for reasons including political instability, little research in the sector and fund mismanagement by authorities.

Recommendations

Developing countries should implement public-private partnerships in energy projects.

Increase financing in energy sector by encouraging investors,

Incorporate Research & Development and adopt clean technology to decarbonize energy systems.

References

https://www.irena.org/Data/View-data-by-topic/Finance-and-Investment/Renewable-Energy-Finance-Flows

Legros, S., Mialet-Serra, I., Clément-Vidal, A., Caliman, J. P., Siregar, F. A., Fabre, D., & Dingkuhn, M. (2009). Role of transitory carbon reserves during adjustment to climate variability and source–sink imbalances in oil palm (Elaeis guineensis). Tree Physiology, 29(10), 1199-1211.

Wen, H., Chen, S., & Lee, C. C. (2023). Impact of low-carbon city construction on financing, investment, and total factor productivity of energy-intensive enterprises. Energy J, 44(2), 51-74.

Ren, X., Li, J., He, F., & Lucey, B. (2023). Impact of climate policy uncertainty on traditional energy and green markets: Evidence from time-varying granger tests. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 173, 113058.